Party politics & Indian public opinion toward the Six Days War

Aidan Milliff and I have been working for years on a project about Indian public opinion toward foreign policy (hopefully someday coming to a scholarly outlet near you!), and part of it involves going through decades worth of historical surveys done by the Indian Institute for Public Opinion.

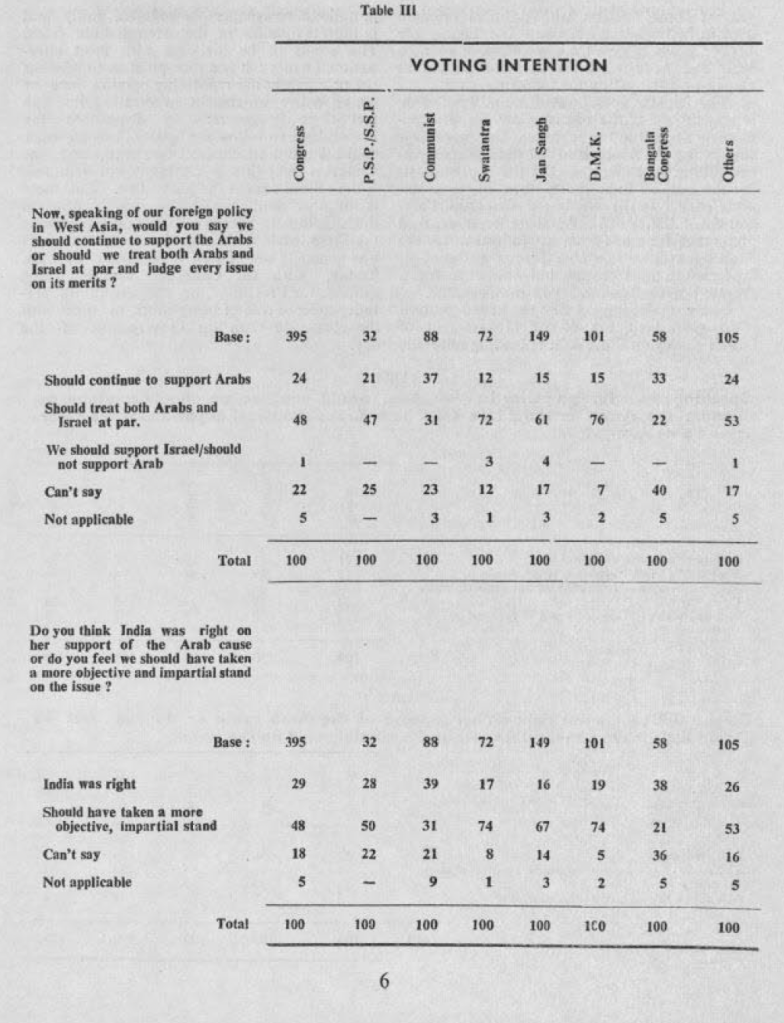

This is an interesting IIOPO survey on Indian views of the government’s policy toward the 1967 crisis/war in the Middle East in July 1967 among respondents in four metros (Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Mumbai), broken down by expressed voting intention. While in most of our work we are not seeing consistent partisan differences in foreign policy views (i.e. in views of the US or USSR/Russia), this is one in which we do see some differences between parties and general ideological inclinations (i.e. compare Swatantra and Jan Sangh to Congress and especially Communists).

Released from the burden of my past. July 23, 2024.

Myanmar’s humanitarian crisis

A sobering overview by Shoona Loong at IISS (the link also includes valuable maps, part of IISS’s excellent mapping of the conflict):

“In the post-coup context, the SAC’s counter-insurgency campaigns against People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) have differed from its campaigns against ethnic armed organisations (EAOs). In the central Dry Zone, a predominantly Bamar-Buddhist area where PDFs largely fend for themselves in battle, SAC foot soldiers have intensively targeted the civilian population through a mass campaign of arson. In the borderlands where more powerful EAOs operate, the SAC’s use of arson is more limited. Instead, communities in EAO areas face other forms of collective punishment, such as blockades and indiscriminate shelling. . . .

The burning of homes and civilian infrastructure has contributed to soaring rates of internal displacement in areas far from Myanmar’s external borders. These arson campaigns are concentrated in the Dry Zone, particularly Sagaing region. In the first two years after the coup, Data for Myanmar reported that nearly 80% of the 55,000 homes that had burned down were in Sagaing. The UNOCHA reported no displacement in Sagaing before the coup; now, estimates of the number of internally displaced people there range from one million to over two million, more than in any other state or region. . . .

the humanitarian crisis in the Dry Zone can be understood not as an after-effect of the conflict but as part of the regime’s strategy of draining PDFs of civilian support by breaking their will to resist. Although over the years the military has wielded this strategy — inaugurated six decades ago as the ‘four cuts’ counterinsurgency doctrine — against legion enemies, it has found its clearest and most brutal expression in the Dry Zone since the coup. . . .

The Institute of Strategy and Policy — Myanmar (ISP) reported in late 2023 that more than one million refugees had fled from Myanmar since the coup. Adding to this the number of people who have left Myanmar because of the political and economic instability caused by years of fighting, the total could be several times higher. . . .

The coup has left nearly one million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, most of whom fled before 2021, with no good options. On one hand, the conflict in Myanmar has eliminated the possibility of return and citizenship for Rohingya in the short term, especially since the military that expelled Rohingya from Rakhine seven years ago is now in power. On the other hand, the scale of displacement across this border, and Dhaka’s unwillingness to integrate refugees into the local population, has resulted in Rohingya refugees facing intense overcrowding and spiralling violence in the camps.”

“Blowtorch Bob” on India and Nepal in 1962

“Blowtorch Bob” Komer is well known for his work – and writing about – internal security and pacification in South Vietnam in the mid/late-1960s (his book Bureaucracy Does Its Thing is a classic). But he was on the NSC doing other stuff in the early 1960s, including providing background on India-Nepal relations here in 1962 (from the JFK presidential papers). The context is that King Mahendra took power from an elected government, whose party the Indians were then supporting as exiles, about which Mahendra was angry. After the India-China war later in 1962, the Indians shut down active raids across the border, but this was just prior when tensions were high.

Here is his standardly-caustic take on the situation: Mahendra is “another little King whose tough-mindedness exceeds his common sense” who is “playing footsie with the Chinese” while “our people. . . think Indian policy pretty footless and have counseled moderation, but you know Indians.” Easy to see how he got his nickname.

Eisenhower talks hunting in Nepal

Amusing little paragraph from a summary of the September 22, 1960 meeting between Eisenhower, Nepali PM BP Koirala, and the Nepali ambassador to the US:

“The Prime Minister said that Nepal was an interesting country and he hoped it would be possible for the President to visit Nepal someday. The President replied that so far as hunting was concerned, he did not like to kill anything larger than birds. The Nepalese Ambassador intervened at this point to say: “But we have birds, too!” The Prime Minister implied that there was more than hunting to be done in Nepal.”