A book I am finding incredibly interesting

Rex Mortimer, Indonesian Communism Under Suharto: Ideology and Politics, 1959-65. A fascinating narrative of the PKI’s strategies, ideologies, and goals under Sukarno as it tried to carve out a path to power while navigating a tumultuous international situation and complex internal political competition. Part of my current book research on 1950s-1960s Indonesia in comparative perspective.

“The Country That Bombs Its Own People”

A grim, excellent report from the New York Times using a variety of methods to show how Myanmar’s military is engaging in pervasive civilian targeting:

“Internet shutdowns and digital surveillance prevent much information from trickling beyond Myanmar’s borders. But behind the veil of secrecy, the military is carrying out a devastating and indiscriminate campaign of violence.”

Pritzker Pavilion. July 29, 2023.

Manipur overview

The violence in Manipur has been a bit hard to get a handle on from a distance, especially since I have always found it the most challenging case to understand in the Northeast in general. Despite some quibbles (actually very few NE insurgencies had their start “soon after independence”), the International Crisis Group has a new report that provides an extremely valuable overview of how the state got to this point. Go check it out.

Civil-military relations after Jokowi

A new report by the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict:

“explores the consequences of Jokowi’s lack of interest in keeping the military in check and what the consequences could be if Prabowo, now a candidate for president, is elected in 2024.

The backsliding on civilian control has involved opening up more and more civilian positions to active-duty officers, replacing civilian defence ministers and many of their subordinates with retired officers, expanding the TNI’s non-military roles, expanding its territorial command structure, and failing to subject military budgets and procurement procedures to close scrutiny.

These developments have often served Jokowi’s interests of building a circle of trusted allies, expanding his political coalition, and encouraging faster and more efficient infrastructure development. He has been aided in his reliance on the military by the TNI’s generally positive image among the Indonesian public.

The report notes that while the interests of the TNI as an institution and Prabowo Subianto as Defence Minister and political candidate do not always coincide – indeed are often at odds – Prabowo as president could seek to further expand the military budget, territorial commands, and some internal security functions. He is on record as advocating an increase in the number of regional military commands from the current 15 to 38 – meaning one in every province.

Under the circumstances, the report notes, the most effective check on military power will lie in the national parliament and a strong political opposition.”

Watch photography is really hard. July 20, 2023.

Brazinsky on US-China competition in the Cold War

An important passage from his Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War, and one very relevant to contemporary Asia – while regional states are much more stable today, they remains outside the reliable control of outsiders:

“political instability prevailed in much of the Global South during the Cold War often confounding the efforts of both Americans and Chinese to cultivate particular leaders or elites. Military coups, successful insurgencies, or other power plays could realign politics in developing countries, altering relations with and perceptions of outside powers” (9)

Indian public opinion toward the US in 2023

Pew has another excellent survey out looking at a variety of countries’ public opinion toward the US. Luckily this one includes India. What do Indians make of the US and Joe Biden?

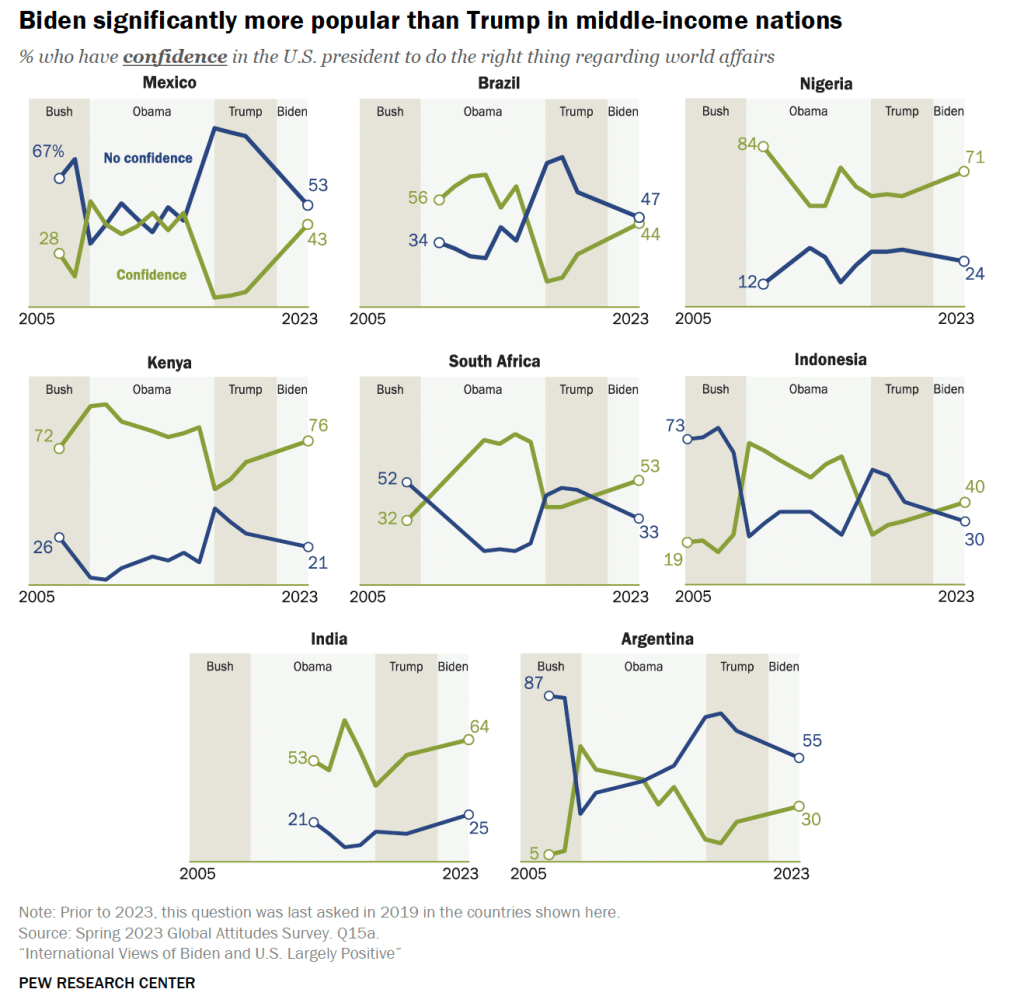

First off, public opinion toward Biden is overall very positive, continuing an upward trend since 2017 (and returning to close to the Obama-era high):

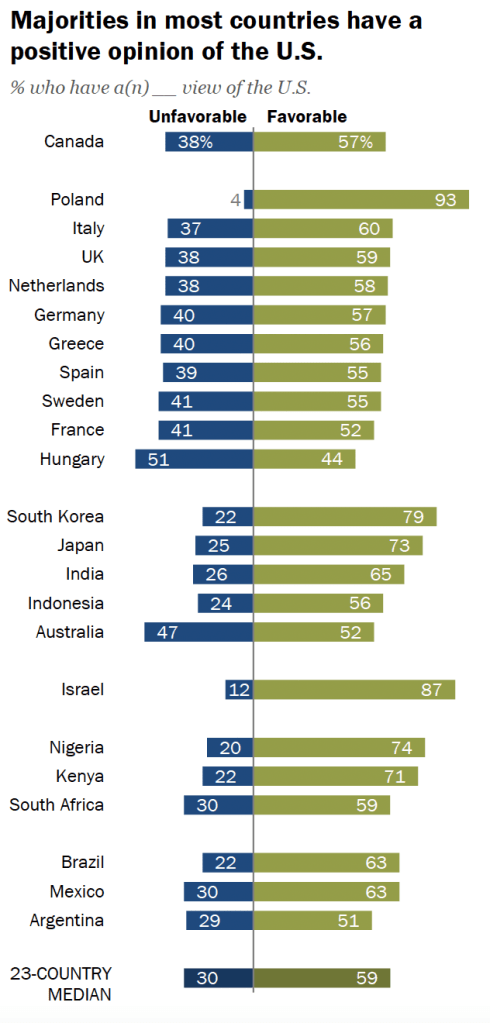

Second, Indians have a generally positive opinion of the US in general:

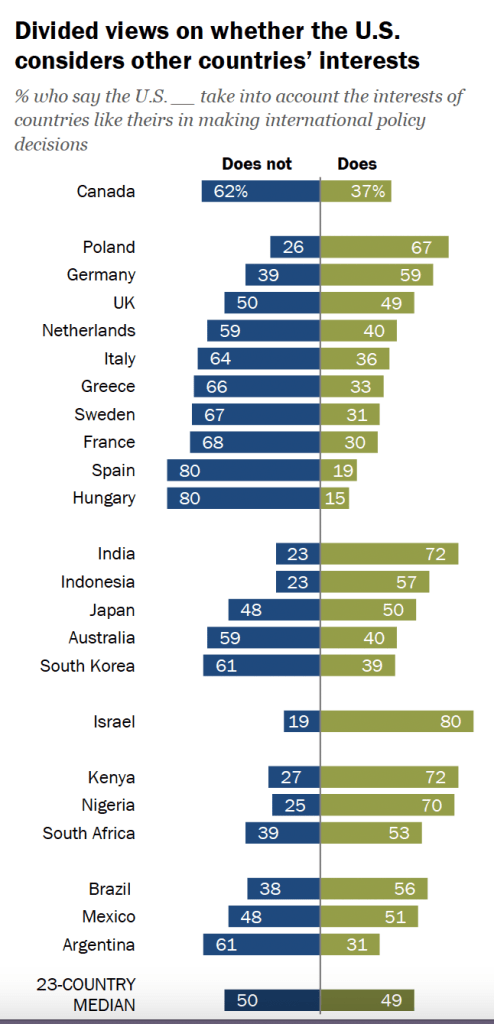

Third, an unusually high percentage of Indians think the US considers their country’s interests (Indians also overwhelmingly think the US contributes to peace and stability around the world, at 70%):

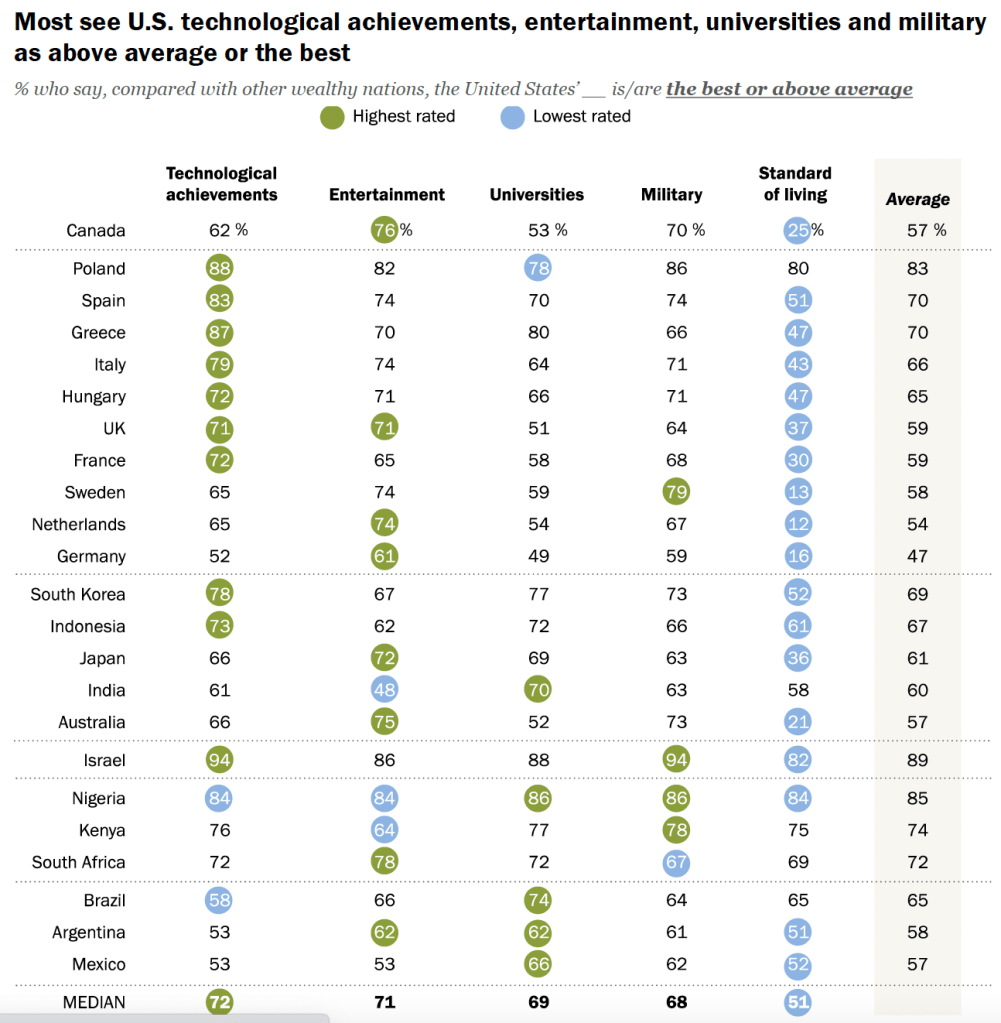

Fourth, Indians are impressed with American universities and unimpressed with American media and entertainment (note: I agree!):

The trends here look very good for the United States and US-India relations. They are also a useful reminder – including to me – that the daily outrage on twitter (how dare the US send Uzra Zeya to Delhi (to, it turns out, talk about the Indo-Pacific strategy)! Blinken’s comments on human rights will turn Indian opinion against the US! Biden is trying to soft regime change Modi!) seem to be largely irrelevant to mass public opinion. They may matter to a (likely very small) subset of the public, of course, and that can be meaningful, but most people aren’t paying attention or experiencing radical swings in opinion. The same is true in the US – 40% of Americans haven’t heard of Modi one way or another while general opinion toward India seems pretty stably positive. Most of this day-to-day stuff that occupies wonks and twitterati and journalists and academics is irrelevant to public opinion. It may be relevant in other meaningful spheres (legislatures, NGOs, The Discourse, etc) but it’s important to keep some perspective.