(for an article about the bee, see this Sun-Times article)

(for an article about the bee, see this Sun-Times article)

I’m spending a lot of time right now understanding Laos’ fairly quick descent into militarized polarization during the early Cold War, which occurred much faster than in Cambodia. This is not a case I knew anything about prior to starting the work, so it’s been a really rewarding and interesting experience to hit something genuinely new.

Below are a few books I’ve found useful (with deep debts to the H-Diplo roundtable review of Seth Jacobs’ The Universe Unraveling as a guide):

Christopher E. Goscha and Karine Laplante, eds., L’échec de La Paix En Indochine/The Failure of Peace in Indochina: 1954-1962 (Paris: Les Indes Savantes, 2010)

Martin Stuart-Fox, A History of Laos (Cambridge, U.K. ; New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

MacAlister Brown and Joseph Jermiah Zasloff, Apprentice Revolutionaries: The Communist Movement in Laos, 1930-1985 (Hoover Institution Press, 1986)

William J. Rust, Before the Quagmire: American Intervention in Laos, 1954-1961 (Lexington, Ky: University Press of Kentucky, 2012)

Nicholas Tarling, Britain and the Neutralisation of Laos (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011)

Martin Stuart-Fox, Buddhist Kingdom, Marxist State: The Making of Modern Laos, 1st ed, Studies in Southeast Asian History, no. 2 (Bangkok ; Cheney: White Lotus, 1996)

Arthur J. Dommen, Conflict in Laos: The Politics of Neutralization, Rev. ed (New York: Praeger, 1971)

Søren Ivarsson, Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space between Indochina and Siam, 1860-1945, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Monograph Series 112 (Copenhagen S, Denmark: NIAS Press, 2008)

Jacob Van Staaveren, Interdiction in Southern Laos, 1960-1968: The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia (Washington, D.C: Center for Air Force History : For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O, 1993)

Lawrence Freedman, Kennedy’s Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Vatthana Pholsena, Post-War Laos: The Politics of Culture, History, and Identity (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 2006)

William J. Rust, So Much to Lose: John F. Kennedy and American Policy in Laos, Studies in Conflict, Diplomacy, and Peace (Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2014)

Seth Jacobs, The Universe Unraveling: American Foreign Policy in Cold War Laos, Illustrated edition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012)

Jane Hamilton-Merritt, Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942-1992 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993)

Charles A. Stevenson, The End of Nowhere: American Policy toward Laos since 1954 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972)

Qiang Zhai, China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950-1975, First Edition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000)

Ryan Wolfson-Ford, Forsaken Causes: Liberal Democracy and Anticommunism in Cold War Laos (University of Wisconsin Press, 2024

The National Archives of India has a portal named Abhilekh Patal. It’s become increasingly useful over the years (especially once I learned how to search it properly). While sometimes buggy to use, the quantity of uploaded material has dramatically grown and I really appreciate the access to Indian primary sources it allows. Recently, it seems to be using OCR, which can lead to errors in titles, as you’ll see below, but on balance seems very useful and positive. I’ve very extensively used Indian sources from its Kathmandu embassy in the 1950s and 1960s.

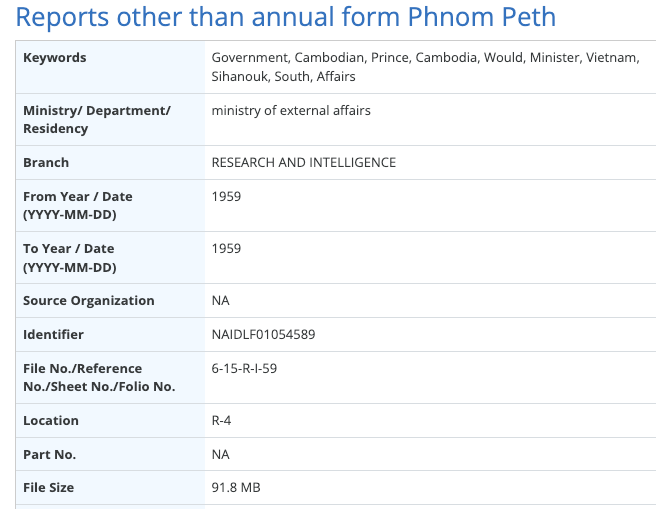

I also now see that several files from the Indian ambassador in Phnom Penh have been uploaded. India was quite involved in Southeast Asia in the 1950s/1960s (in part because of its key role on the International Control Commission), and there is some fascinating stuff in these files. There are also some reports from Laos in the late 1960s that look really interesting. The thing to search for is “Political reports other than annual” or some version thereof – these tend to be monthly assessments of the country in question’s internal and external politics; the annual reports, by contrast, are data on embassy staffing, activities, budget, etc.

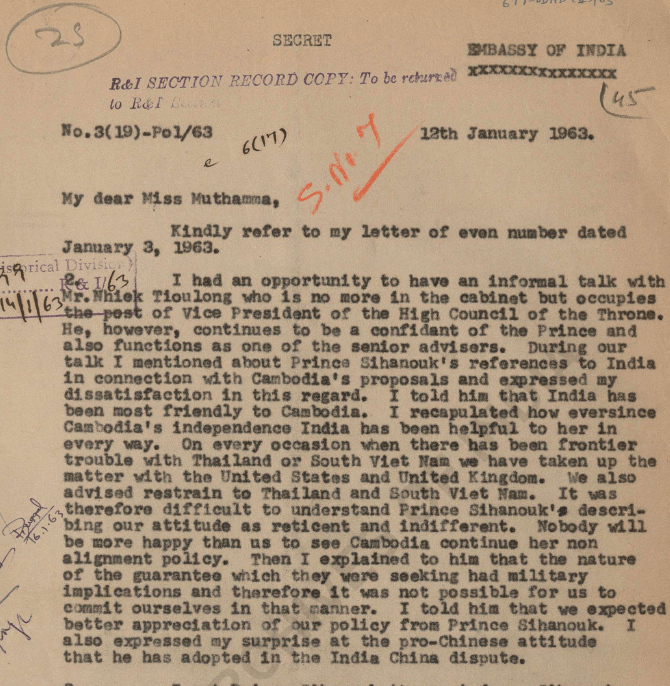

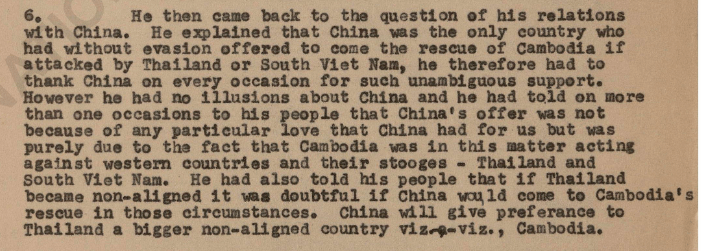

I’ve never figured out how to create a durable permalink to individual records, so I’ve copied screenshots below to help people find them. I’ve also included an excerpt of a summary of a conversation between Prince Sihanouk and Raghunath Sinha, the Indian ambassador to Cambodia at the time, in which Sinha expresses his concerns over his tilt to China.

Parts of a letter back to Delhi from the Indian ambassador:

Some screenshots of the files themselves (note the incorrect title spellings – I think this is the AI/OCR at work, but it also OCRs the entire full text so searches go to the right files)

Akhilesh Upadhyay has a valuable piece in the Hindustan Times on the implications of radical shifts in US aid under the Trump administration:

“America partners with the Nepal government and local organisations on a wide range of programmes—from boosting food security and economic growth, managing natural resources, improving health care and education and bolstering democratic governance and responding to natural disasters. Nepal has been a major recipient of aid from the US, the largest donor globally. In fiscal year 2023, it disbursed $72 billion worldwide. . . .

Already, some organisations have been forced to lay off their staff while many others are bracing for a protracted suspension. The worst-hit are those which are fully funded by American assistance. But all — regardless of whether they are fully or partially funded — now seem pressured to diversify their resources. A senior member of a civil society organisation working on climate change said his office has laid off some of their Kathmandu-based staff, and the remaining members of the team have agreed to take a 20% pay cut to stay afloat. Efforts were now afoot to diversify aid sources.. . . Fast forward to 2022, USAID signed a five-year “strategic plan” with the Nepal government, committing $659 million. The agreement outlines the broad development areas of cooperation and collaboration and supports Nepal’s goal of graduating to a middle-income country, working in partnership with the government, civil society and the private sector. The emphasis is on strengthening democratic governance, enterprise-driven economic growth and increased resilience for communities most at-risk to natural disasters and climate change. But questions have arisen about whether Trump 2.0 has any appetite for these programmes, including the idea of inclusion, a cardinal political pillar of Nepal’s new constitution and polity post-2006. . . . .

By all accounts, however, the 90-day hiatus will not impact the US-assisted Millenium Challenge Corporation’s (“MCC”) Nepal Compact — the single largest grant Nepal has ever received. The aid is being used for building transmission lines and improving roads. Nepal contributes $197 million to the MCC Compact. If the recent statements from the U.S. government is anything to go by, MCC projects are not in danger. According to a January 26 statement by the State Department, Trump’s executive order “on Reevaluating and Realigning” the foreign assistance only covers those areas “funded by or through the State Department and USAID.” . . . .

For now, however, the suspension of US aid has sparked significant discussion on Nepal’s social media and in the press, reflecting public concern over the potential negative impact on essential services and development projects. Significantly, the recent shifts in American foreign policy have resulted in new small-state anxieties in Nepal, just as in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, that far outweigh the development budget Trump’s move has put on hold. To many in Nepal, the possibility of the aid withdrawal by America, or ‘Third Neighbour,” could lead to even greater reliance on two immediate ones — India and China in the long term. America’s great-power rival, China might even relish this prospect in the South Asian theatre.”

In 1958 (and afterwards – things would get very bad in 1959 for instance), Cambodia had tense and conflictual relations with South Vietnam. Within this context, an exchange of cables in July 1958 provides a great example of US ambassadors in rival capital cities taking sides against the other’s country.

First we have Carl Strom, US ambassador to Cambodia, frustrated with South Vietnam and US policy toward it:

“Phnom Penh, July 7, 1958—5 p.m.

30. It is difficult to sort out the many things that have happened last few days but one fact seems to emerge prominently, namely, that Cambodia is at a crossroads. I am convinced Sihanouk has wanted and still wants a solution of his problems with Vietnam through the instrumentality of Western powers. Considerable evidence is accumulating that he is playing with the idea of support of some kind from Red China but I am still sure he believes that Cambodia’s true friends are in the West and that a closer approach to Communist bloc would be basically distasteful to him.

However, Sihanouk feels put upon and abandoned. He believes that Cambodia’s Western friends have been indifferent in his time of trouble. .. .

The solution of this problem would clearly seem to be settlement between Cambodia and Vietnam. This is desired by all the Western powers represented here, US, UK, France and Australia, and certainly by Cambodia. Sihanouk seemed to have removed the greatest difficulty, namely the question of who should make the first approach, by volunteering to go to Saigon. However, after having been told he would be received, whole project fell through as result bitter and vicious attack on Sihanouk in semi-official Vietnam Presse July 3.2GVN Foreign Minister issued official communiqué July 6 whose first paragraph was mollifying in tone but which in its effect did not improve situation (Saigon’s 31 to Department).3

I have twice recommended US intervene in strong and unequivocal fashion with GVN to require them to settle their difficulties with Cambodia.4 Department has replied that US cannot tell GVN what to do.5 However, in absence firm action by US, GVN has acted and, in effect, established policy for West vis-à-vis Cambodia which is exactly contrary to policy desired by all Western powers represented here. Even if negotiations can be rescheduled, they will not succeed unless Diem can be persuaded GVN’s self-interest makes success desirable. I [Page 235]do not believe we have any choice except to present matter to Diem as vital to his own interest and to that of West and to insist on negotiations with Cambodia in good faith.”

Then Elbridge Durbow, ambassador in Saigon, fires back:

“Saigon, July 9, 1958—7 p.m.

60. Following are my considered comments on Phnom Penh’s telegram 302 as requested by Deptel 36.

From here Cambodia does not appear to be at crossroads but rather somewhat past that point along road to left. Sihanouk has already recognized USSR and accepted Soviet aid and for most practical purposes has also recognized Communist China by accepting trade mission and considerable ChiCom aid. . . .

I translate Sihanouk’s talk about “pure” neutrality and “active” neutrality as nothing more than “pure” opportunism or smokescreen (see Phnom Penh’s telegram 27 numbered paragraph 5).4

To me Sihanouk’s talk about friends and allies in his July 5 speech is nothing but a part of smokescreen or crude blackmail attempt and his remarks accusing us of sabotaging his meeting with Diem are insulting and call for very sharp protest. . . .

Although I have repeatedly urged Diem and other GVN officials to exercise restraint and moderation in dealing with Cambodia and they have not been helpful, particularly in July 3 and 4 press articles, I have personal conviction that Sihanouk for whatever motives he may have has deliberately elected to exacerbate Cambodian-Vietnamese relations and that time has clearly come for us to call his bluff. . . .

If Cambodia wants to turn increasingly to Communist China that is her privilege but RKG must not expect us to enter bidding contest with Communists but rather must expect that US would be obliged to re-examine its aid policy. We should also talk to Diem firmly along lines 1, 2 and 4 above.5

If, as may be case, Sihanouk is drifting more and more towards Communist China any efforts to appease him will only encourage him in his game of playing both ends against the middle. On the other hand if we bring him up abruptly I think we have a good chance of making him face situation with greater realism.”

This tension about how to approach Sihanouk’s neutralism in Cambodia would be recurrent over the next decade, with sympathizers of his plight urging flexibility and understanding, and skeptics viewing him as tilting to the Communists (especially the Chinese) and being only encouraged by American understanding.

Arzan Tarapore has a valuable analysis of where India-China ties stand now, and what choices present themselves to India now that there has been some measure of stabilization in the border dispute:

“The lasting impact of the Ladakh crisis should be measured in three dimensions. First, the crisis compelled India to intensify its military balance on the Line of Actual Control, but it remains unclear whether that has strengthened its conventional deterrence against China. Second, the crisis compelled India to reinforce its northern border at the expense of military modernization and naval force projection in the Indian Ocean. It remains to be seen whether that change will be reversed. Finally, the Ladakh crisis cratered India’s relationship with China and nudged it towards closer cooperation with the United States. The trajectory of India’s relations with both Beijing and Washington also remains an open question.

In each of these dimensions, the effects of the crisis between India and China that began in 2020 will be felt for many years.”